Trade vs. Trees: Is the EU’s Deforestation Regulation Being Undercut by Its Own Trade Policy?

Read summarized version with:

Recently, the European Commission presented the EU-Mercosur trade agreement for sign-off by member states after over 25 years of negotiations.

This trade deal, which aims to establish one of the world’s largest free-trade zones, would remove duties on 91% of the bloc’s exports to Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay – all key exporters of high-risk commodities covered by the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR).

While EU trade commissioner Maroš Šefčovič strongly advocated for the deal’s mutual benefits, it raised concerns about its potential implications for the already shaky future of the bloc’s anti-deforestation law.

The EUDR is designed to ensure that commodities such as palm oil, soy, coffee, cocoa, beef, and rubber – and their derivatives sold in the EU are “deforestation-free.” Companies are now obligated to conduct extensive due diligence to prove their products were not sourced from deforested lands, which requires a fresh level of supply chain visibility, including precise geolocation data for the areas where the commodities were produced.

The regulation, which survived last-minute attacks, was finally given the green light a couple of years ago, only to have its application postponed until December 2025. The European Commission recently announced a possible further 12-month delay for the implementation of the EUDR, despite significant investments of time and resources by many companies to prepare for compliance, much like their efforts for the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

When policy weakens regulatory rigor

Now, enter the EU-Mercosur partnership agreement. The deal includes a dedicated chapter on sustainability, with commitments to the Paris Agreement and efforts to combat illegal logging, but it also has inherent risks that could render these pledges ineffective.

The core of the issue is a fundamental conflict of objectives. The trade deal is designed to boost commerce and foster dialogue and cooperation, which will inevitably increase the flow of agricultural products from the Mercosur region into the EU. These commodities are the primary drivers of deforestation and land conversion in South America, threatening not only the Amazon rainforest but also vital ecosystems, including the Cerrado savannah and Gran Chaco forests, which are largely outside the EUDR’s scope.

Furthermore, critics point to the lack of teeth in the agreement’s environmental provisions. The deal’s non-binding commitments on deforestation are less ambitious than some of Brazil’s own national targets, and its provisions could complicate the EUDR’s enforcement. The agreement’s language suggests using information from Mercosur national authorities for verification, which could undermine the EU’s independent and rigorous due diligence requirements. This creates a “due diligence trap,” where companies are caught between a binding EU regulation and a trade agreement that could weaken its implementation.

The true scope of risk: Beyond deforestation compliance

This dilemma is part of a broader, more worrying trend. The recent news of Commissioner Šefčovič’s intervention to stop a penalty against a major US tech company, following threats of tariffs from the US President, illustrates the growing influence of geopolitical pressure on regulatory matters. This suggests that even the EU’s most principled regulations, from digital governance to environmental protection, are susceptible to being softened or delayed in the pursuit of trade diplomacy.

Without a reliable, systematic approach, navigating the EUDR’s stringent requirements in the context of an accelerating EU-Mercosur trade relationship and possible further delays becomes a high-risk gamble. The sheer volume of data required – from precise geolocation to verifiable non-deforestation statements – demands an investment in systems that provide independent and continuously monitored supply chain intelligence.

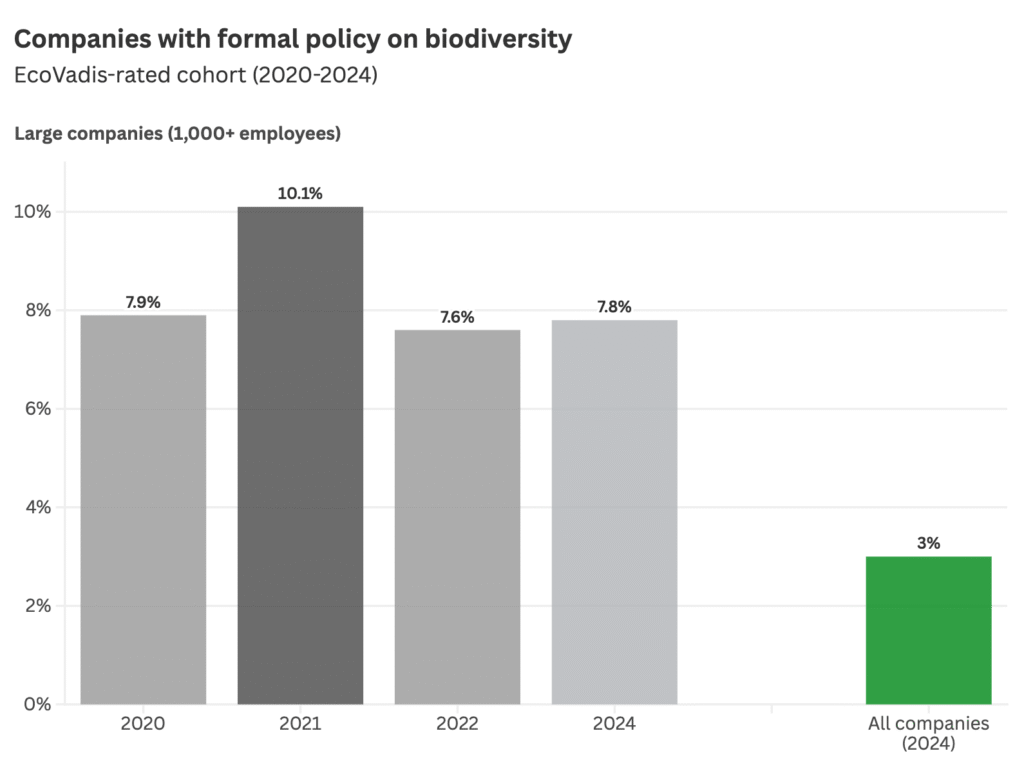

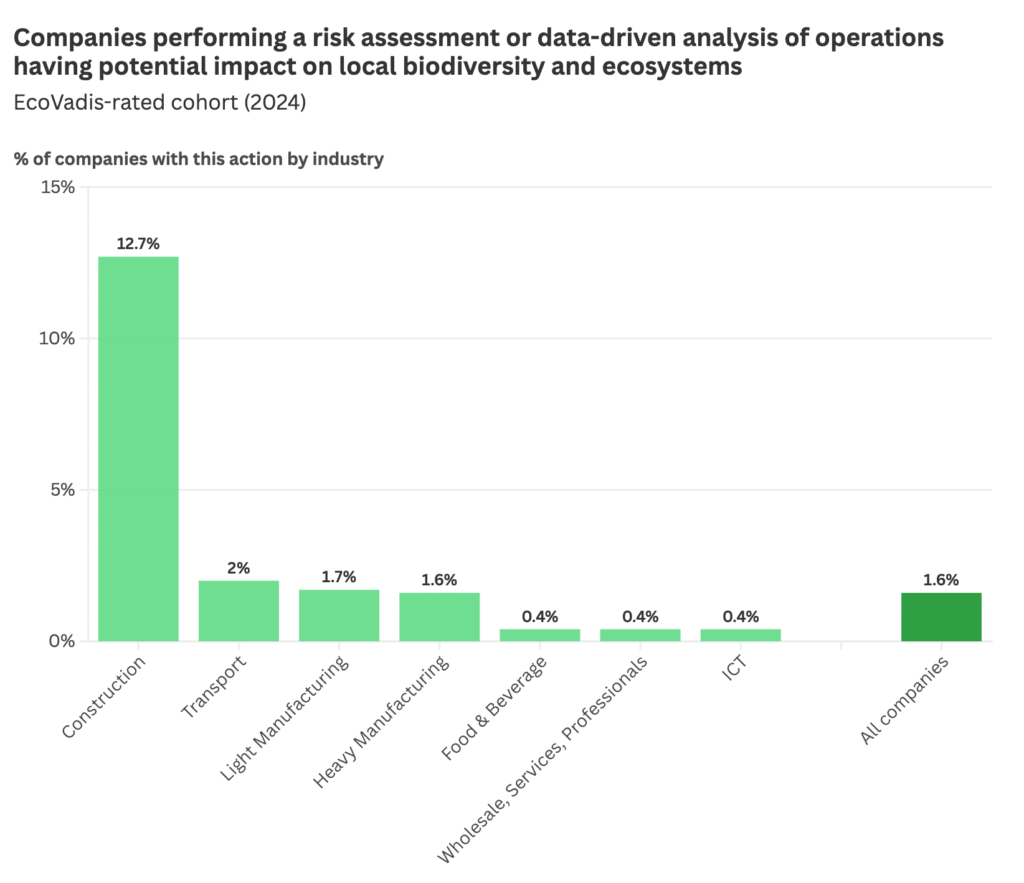

The regulatory and trade volatility further exposes a critical gap in corporate sustainability efforts: the focus on compliance often overshadows the broader environmental and biodiversity mandate. Data from EcoVadis Ratings underscores companies’ limited efforts on biodiversity and ecosystems protection, with historically low rates of policy and action implementation in many high-risk sectors.

Even in sectors highly dependent on land use and raw material extraction, the formal mechanism for assessing biodiversity risk remains insufficient. This demonstrates that while companies may be scrambling to collect geolocation for EUDR compliance, they are neglecting the deeper, systemic nature-related risks that threaten their supply chains just as severely. Stakeholder pressure from investors and consumers will continue to rise on this front, regardless of legislative delays.

This is the new imperative: using data-driven due diligence not only as a regulatory shield, but as the foundation for ethical sourcing and durable commercial success in an increasingly complex world.

ChatGPT

ChatGPT  Gemini

Gemini  Perplexity

Perplexity  Claude

Claude  Grok

Grok